Welcome to the world of William Shakespeare!

This is an accessible in-depth introduction to the genius of the Bard, where I will first examine the genius of the man, his life and times, the language he mastered and of course his legacy – but principally the catalogue of his incomparable works:

38 plays

154 sonnets

several long poems

and 3 lost/disputed works

We will see it all. And welcome – whether you are deeply familiar with his work or simply curious to dip a toe into the warm water of his genius.

A good place to start is with the Seven Stages of Man speech by Jaques, from As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7:

“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.

At first the infant, mewing and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then, the whining school boy with his satchel and shining morning face,

Creeping like snail unwillingly to school.

And then the lover, sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow.

Then a soldier, full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard, (panther like cat)

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation even in the cannon’s mouth.

And then, the justice, in fair round belly, with good capon lined,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances, and so he plays his part.

The sixth age shifts into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacle on nose, and pouch on side,

His youthful hose well saved, a world too wide for his shrunk shank, (loss of verility)

and his big manly voice, turning again toward childish treble,

Pipes and wistles in his sound.

Last scene of all, that ends this strange, eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

In this famous passage Shakespeare has us covered – from the mewing and puking infant to the mere oblivion of childish old age. And there are dozens of passages that impressive in Shakespeare’s plays, about characters spread out over those seven stages of our lives. We will encounter them all.

I believe that the more you see or read the works of William Shakespeare the more you are in awe. It just goes deeper and deeper, and gets richer and richer – the further you delve in, the more comfortable and relaxed you become with the language and the more you merely think about it. How the magnitude of these accomplishments is even possible, after decades of teaching him and years of studying little else, I still find to be an enigma insoluble. It is my belief that Baldolatry, the worship of Shakespeare, is deserving of its status as a secular religion.

No world authors have surpassed Shakespeare in his creation of human personality. He simply wrote the best poetry and the best prose in the English language (or likely any language). He thought more deeply and originally than any other writer. He wrote of the human personality as we continue to know ourselves today, from childhood to old age and every age in between.

His greatest originality was in his representation of insight into personality and character. He was most talented at conjuring up human beings in convincing circumstances.

We owe Shakespeare so very much because he has taught us to understand and appreciate our very own human nature. He wrote about us and depicted us as no one ever has.

And what he represents best of all are human changes, caused by the various flaws in the human will’s many subtle vulnerabilities. Shakespeare presents essential human nature as a universal and timeless phenomenon. The vagaries of human behaviour have never been better portrayed, which is how Shakespeare draws us in and connects us to such powerful emotions.

There are so many characters and themes interwoven into these stories which reveal the primary templates of the human condition. There is no clearer literary body of work that thumbprints the human architypes more comprehensively than the works of William Shakespeare.

His greatest gift was in the rendering of two competing perspectives without revealing the prejudice of either. Shakespeare presented us to ourselves as voluntary undertakings between individuals exercising free will. His theatre became a mirror for everyday life. Watching or reading Shakespeare often makes us recognize that we know more about the characters than they know of themselves or of each other. He presented people revealing very specific aspects of themselves to certain people and not to others, exposing the idea that we are multitudinous complexities.

For instance, he frequently examines what it is like to be in love. It is often very painful and we agonize over it and get frustrated by it and we sometimes give it up only to throw ourselves right back into it again, if and when we are confident (or perhaps needy) enough. Love, like our very nature, is mutable in the extreme. The tumbling, kaleidoscope effect of love is beautifully captured time and time again in his plays, where relationships are difficult and those that start off romantically are most difficult to maintain. He analyzes relationships in all of his plays and places many questions marks around them all for our consideration.

The plays themselves are often beyond the mind’s reach and we can seemingly never catch up with them. Shakespeare continues to explain us to ourselves because…

he invented us as we have come to know ourselves.

This is essentially the central thesis of this blog. In this regard his total effect upon world culture is incalculable.

After Jesus, Hamlet is the most cited figure in Western consciousness. The enigma of Hamlet is emblematic of the greater enigma of Shakespeare himself, an art so infinite that it contains us. There are more Hamlets than there are actors to play him. In Hamlet we see the birth of the modern psyche as it emerges from the Medieval world into an Elizabethan Renaissance of greater individualism and deeper self-consciousness. Hamlet represents a radical transformation of how consciousness and personality are portrayed and this is the single greatest of all Shakespearean originalities. Hamlet glimpses the abyss of human consciousness, or self-awareness, and it terrifies him, as it can still terrify us. Hamlet is deep and his perspectives are many, which help to explain why he changes every time he speaks, and why he is so endlessly fascinating to us, and why we cannot encompass him, and why no two actors, no matter how great, will ever give us the same performance of Hamlet.

Hamlet senses the deep and dangerous infinite that lies within each of us. It is that sense that you can fall down deep inside yourself and get hopelessly lost, disoriented and overwhelmed and never find yourself. You will just keep falling and falling and falling in a 20th century existential type crisis, which is Hamlet’s predicament but is in some sense the predicament of all of the deep souls in Shakespeare. I would suggest it remains the predicament of our times – if not that of all times and all places. The mind is a dangerous thing because, for better or for worse, we think ourselves in and out of so many different situations in our lives. And ‘To be or not to be” is in fact the question, as we choose each moment between complete authenticity or something less. These fantastically compelling dimensions of human self-awareness are very much exemplified by Hamlet (the play) and Hamlet (the character), the truest human being in the entire Shakespeare canon.

The self-awareness of Hamlet and Falstaff render them endless to our meditations. Falstaff finds an avalanche of words for what lives fiercely in his heart and he always glories in the act of being and speaking – using words to teach the things within himself: the incomparable wit, the exuberance, the defiance of time and the sheer joy of being. He manifests that ancient Hebrew blessing: ‘more life!’ Hamlet, by contrast, has no such love of life or of self or of anyone or anything. Their geniuses are wholly unique while they remain the penultimate examples of how Shakespeare literally reads us better than we read him or ourselves.

Essential knowledge in Shakespeare is the comprehension of authentic personhood. Tragedy in Shakespeare turns upon a loss of authenticity that threatens to empty us of meaning and life. What we learn from Shakespeare is the courage to look deeply into the human psyche. No artist has gone so deep with such ruthless examination of peoples’ motives and pretentions. William Shakespeare teaches me, more than anything, the Buddhist ideal of maintaining an unbounded curiosity and openness toward absolutely everything, without judgement. We have become William Shakespeare characters because they are so much like us.

The poet Emerson said that Shakespeare has composed the essential text of modern life. Hegel remarked that Hamlet and Falstaff are ‘free artists of themselves’. And Ben Johnson, Shakespeare’s contemporary, eulogized the Bard as ‘being not just of an age, but for all time’.

Hamlet speaks 1,500 lines of his play’s 4,000 lines, Shakespeare’s most verbose character in his longest play. He baffles us, as real people do. Hamlet seldom means what he says or says what he means. Instead, he is the Western hero of consciousness and invests the power of the poet’s mind over all outward forces. We must read Shakespeare as strenuously as we can, knowing that his plays will read us more energetically still. In fact, they read us definitively. He’s got us down to a tee.

Shakespeare’s works have been termed the ‘Secular Scripture’ and the fixed centre of the Western Canon. His few peers – Homer, the Yahwist, Dante, Proust, William and Henry James, Melville, Chaucer, Cervantes, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Balzac and Dickens – remind us that the representation of human character and fluid personality remains the supreme literary achievement and standard: realistic individuals in storylines and themes we can recognize. Readers and playgoers find more vitality in Shakespeare’s words and the characters who speak them than in any other author, perhaps in all other authors taken and considered together. He has become the first universal author. His plays always remain open to radical interpretation. There are rarely ever any stage directions or indications for actors on how they should depict their character. He wrote them to be precisely that, in a real sense unfinished, so that every actor and director, every new time and place can read into the plays the preoccupation of their own age, enabling him to hold up a mirror to all generations, wherein we see our own true reflections.

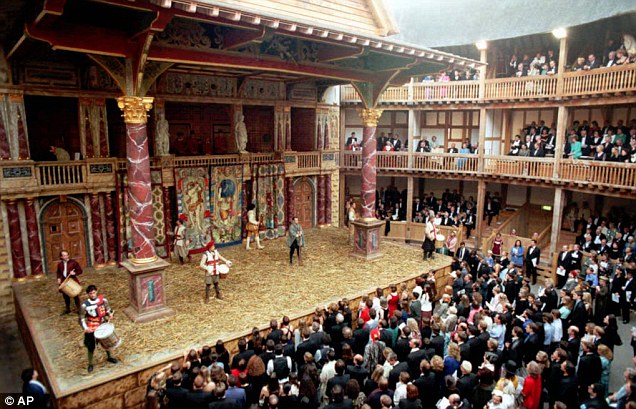

And the profundity of ideas allows for translation into any and all languages. In 2012 the Globe Theatre put together a six-week festival called Globe to Globe, within which they presented all 37 plays, each in a different language and each by a different theatre company from around the world. In 2014 the Globe’s Artistic Director staged Hamlet at the Globe itself in London before embarking on a most remarkable tour intended to share Shakespeare and Hamlet with the world for the 450th anniversary of his birth. Over two years and 19,000 miles the play was presented to 197 nations, demonstrating the power of Shakespeare and Hamlet to transcend modern borders and touch the lives of people on all continents. In Bejing, Sudan, in Syrian refugee camps and on remote islands, crowds filled makeshift theatres to see the Prince of Denmark. No one else gives us so much of the world or of ourselves. Our ideas as to what makes the self authentically human owe more to Shakespeare than ought to be possible. He extensively informs the English language we speak and his principle storylines and characters have become our collective mythology.

The answer to the question “why Shakespeare?’ is simple: Who else is there? The most useful reflection about Shakespeare is his superiority of intellect. No writer is equal to Shakespeare as an intellect. I have read, studied and taught Shakespeare almost daily for many years and I am certain that I see him only darkly. Shakespeare brings to mind what we could not find without Shakespeare. In William Shakespeare’s plays you are prevented from arriving at easy or comforting certainties. Everything you think you understand is challenged. Everything keeps shifting from perspective to perspective. He makes you think without ever telling you what to think. He merely insists THAT you think.

Will Shakespeare presents a very deep and insightful account of diverse human characters and their experiences. And when you possess the power of language that beautiful it presents profound insights of great significance in whatever is said. That is the great power of William Shakespeare and why I constantly return to drink, as from a fountain. He managed to put into words profound truths in exquisite language that people have never managed to express before or since. Shakespeare remains way out ahead when it comes to expressing himself about despair, desire, death, passion, love, forgiveness, suffering, villainy, reconciliation, friendship, inner turmoil, jealousy, ambition, rage, guilt, madness, sexuality, private vice, lust, tragic flaws, artificialities, revenge, honour, marriage, etc, etc, etc…. Characters express everything from all points of view and this is hopefully what we are struck by when we see or read his plays. He remains endlessly relevant. It matters not that he is a 400 year old dead Englishman. In passages, narratives, characters and themes we can readily recognize ourselves, our circumstances and our pathways to greater and deeper understanding and appreciation of our lives.

No other writer, before or after Shakespeare, has ever accomplished the miracle of having created such utterly unique voices for his over 100 major characters and many hundred minor personages. Two characters were easily the most famous and popular in Shakespeare’s time and they remain so today. Indeed, Shakespeare’s own audiences preferred Hamlet and Falstaff to all of his other characters, and so do we, because Fat Jack and the Prince of Denmark manifest the most comprehensive consciousnesses in all of world literature, larger than any of the genius creations of his literary peers. They are palpably superior to everyone whom they, and we, encounter in their own plays and beyond. Falstaff and Hamlet represent the invention of the human and the inauguration of personality as we have come to recognize it in literature and in life. Personality, in our sense, is a Shakespearean invention and is the authentic cause of his lasting pervasiveness.

We are all heirs to Falstaff and Hamlet and so many other characters and personalities that crowd his stage. For Hamlet the self is an abyss, a chaos of virtual nothingness. For Falstaff the self is everything. Shakespeare may not have been merely imitating life but rather creating it in most of his finest works.

Shakespeare’s uncanny power in the rendering of personality and character is perhaps beyond explanation. His characters seem like real persons to us. Hamlet is an agent, not merely an effect, of clashing realizations. Shakespeare made Hamlet free by making him know a truth too intolerable for us to endure. And yet we recognize something of ourselves in him. That’s us. That’s me! Hamlet is not just the Prince of Denmark. Because of the commonalities of the human heart and soul Shakespeare can put us into every one of his characters and settings. Hamlet and I are both trapped on the wheel of timeless humanity, enduring all of the same triumphs and tragedies on so many levels.

Indeed, Hamlet may be the most important play and character of them all. It could well represent the pivot of Shakespeare’s career in the theatre. Macbeth, Lear and Othello will soon follow its creation, as if unleashed by Hamlet, which represents a volcanic eruption of new language.

Over 600 new words and expressions spring from Hamlet alone.

The murder of Hamlet’s father is his secret, learned from the ghost of his dead father himself, if that is in fact who the ghost truly is. And then he pretends to go mad. Or is he truly mad? Polonius points out that ‘there is method to his madness.’ Freud referred to Hamlet as ‘the bone in the throat of Western Civilization’. The poet Shelley claimed that Shakespeare created forms more real than living men we encounter in every-day life. Alexander Pope commented that ‘every single character in Shakespeare’s work is as much an individual as in life itself. It is just as impossible to find any two alike.’

Falstaff is rammed with life, as are the murderous villains Richard III and Macbeth. Exuberance is as marked in Shakespeare as it is in Blake and Joyce. Only Cleopatra and the strongest Shakespearean villains – like Richard III and Macbeth – have the staying force or the wit and intellectual intensity of Falstaff and Hamlet.

Shakespeare’s plays live not merely for the dazzle of language – where hardly a single word is ever lazily used – or the dynamism or fascination of the story telling, but for the way he roots profound moral, ethical and spiritual matters in the everyday reality of character’s lives. At the heart of his plays, real people, with all of their many contradictions, are placed in specific and meticulously realized social environments – worlds we, and people of all places and times, readily recognize. The plays provide images of the deepest truths. Shakespeare creates the illusion of life stretching out in every direction. Poetic, learned, witty and profound passages in the plays are never merely pasted on, but spring naturally from the character’s own feelings in each moment. This is the quality which speaks to generation upon generation, to people of every nationality and creed, guaranteeing the vitality of his plays and their continuing resonance.

William Shakespeare is among the most influential persons who have ever lived. The effects of his words on the world is beyond all proportion in their consequences and surely far beyond anything he himself could have possibly imagined or predicted. His power is evident everywhere, if you know where to look. Performed all over the world in every language, to an extent we find hard to explain, he dramatizes the things that matter most dearly to human beings. There is no other author who achieves this. His great genius was the ability to observe people and situations as they really are and yet not be the least bit judgmental about them. He could put himself in the souls of his many characters, young or old, male or female, hero or villain, fools or kings. He was all of these people in an infinite variety of relationships. And yet we never really know what he himself thinks about anything. He simply leaves us face to face with all of the dilemmas in his work, as he thinks through everything from all sides and leaves us to find our own meaning in the face of it all.

To people unfamiliar with his genius his very name can produce a vague impression of British stuffiness. But the truth is that he belongs absolutely to our world, our lives, our moments and our experiences. The worlds he created and inhabited are both filthy and exalted, cheap and rarified, vile and gorgeous, full of confusions and bursting with epiphanies; in short, they are as full and as complicated as our own. Nothing in literature captures the cacophony of voices and perspectives more than the plays of William Shakespeare. He is more than ever our contemporary, so that when you become familiar with his work, you see him everywhere. He is like that witty friend constantly making the perfect aside on whatever action the world is performing and the breadth and depth of his appeal verges on the bizarre.

Shakespeare’s sophisticated word play is mesmerizing. The very flexibility of language for each individual character is what grants them their distinct voices. Scholars agree that Shakespeare coined somewhere in the vicinity of 2,000-3,000 words, far more than any writer in any language. He is, as Virginia Woolf put it, ‘the word-coining genius.’ His countless original expressions include ‘its Greek to me’, ‘more sinned against than sinning’, ‘your salad days’, ’vanished into thin air’, ’refused to budge an inch’, ‘wear your heart upon your sleeve’, ’suffered from green eyed jealousy’, ’played fast and loose’, ’tongue tied’, ’a tower of strength’, ’hoodwinked’, ‘in a pickle’, ‘knitted your brow’, ‘made a virtue of necessity’, ‘insisted on fair play’, ‘slept not one wink’, ‘laughed yourself into stitches’, ‘too much of a good thing’, ‘seen better days’, ‘lived in a fool’s paradise’, ‘be that as it may’, ‘a foregone conclusion’, ‘it is high time’, ‘the long and short of it’, ‘what fools these mortals be’, ‘your own flesh and blood’, ‘suspect foul play’, ‘rhyme without reason’, ‘give the devil his due’, ‘tell the truth and shame the devil’, ‘uneasy lies the head that wears the crown’, ‘if the truth be known’, ‘bid me good riddance’, ‘send me packing’, ‘dead as a doornail’, ‘an eye sore’, ‘a laughing stock’, ‘a blinking idiot’, ‘the game is up’, ‘the devil incarnate’, ‘by Jove’, ‘tut tut tut’, ‘for goodness sakes’, ‘cold comfort’, and ‘what the dickens’, to name but a few. (And Shakespeare tends to put his wisest expressions into the mouths of his fools, blithering idiots and nastiest villains.)

His impact upon our speech is among the greatest of his powers. He has altered the horizons of thought for billions through his wit, his words, expressions and linguistic dexterity. In the end, Shakespeare is his words. He even managed to place his name in the Bible, (‘for goodness sake!’) King James commissioned the first great English Bible in 1604 and many of the English poets, scholars and writers of the day were invited to contribute. It was not until late in the 20th century that someone noticed overwhelming evidence that Will Shakespeare had worked on the psalms, which makes perfect sense once you have read his sonnets. Shakespeare was 46 years old when he would have worked on the psalms and if you look closely at psalm 46 of the King James Bible you might notice, as someone did, that the 46th word in from the top is ‘Shake’ and that the 46th word in from the bottom is ‘Spear’. I suggest to you that William Shakespeare, great wit, jokester and punster, quietly, in 1607, unbeknownst to the world for over 300 years, actually wrote himself into the Bible.

Shakespeare arrived on the literary scene at a critical turning point in the history of the English language with the gift of stunningly beautiful language and a powerful imagination, depicting human beings in every conceivable situation. He wrote at a time of great political, cultural and linguistic expansion. The English language was being reinvented with great vigor as Elizabethan England played an increasingly important role on the world stage. Thousands of new words were emerging and there was not even a dictionary until 1604. Shakespeare was at the helm of this linguistic explosion. Where he is inconceivably a pure stream of white light and has never been remotely matched, is in the ability to reveal the human condition and character, through unbelievable use of a language that was hardly yet formed. He created a disproportionate number of all the words in the English language. He took language like clay and bent and twisted it to his liking. 20,000 different words were used in his written vocabulary. The average Oxford / Cambridge graduate’s vocabulary is 3,000 words, similar to the number of words Shakespeare himself invented. He created images of things previously inexpressible. Few people are aware of how much our language owes to William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare was excessive about sex and violence. His plays are peppered with dirty jokes and bawdy humour that can still make us blush. Shakespeare wrote about it all… just before and after 1600. He had no time for Puritans and never missed a chance to mock them on stage, as we will see in Twelfth Night. He came by his hatred of Puritans honestly. After all, they were trying to destroy his livelihood, constantly opposing the very idea of the theatre (which they will finally abolish 25 years after Shakespeare’s death). Shakespeare’s theatre was a place of thrusting bodies and the mayhem of their consequences. He was a very sexy writer, centuries ahead of his times. Freud’s frankness around sex may have been his greatest achievement – it changed the private life of the 20th century – and one of Freud’s major sources was Shakespeare. “Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased?” Macbeth begs his wife’s doctor. “Therein the patient must minister to herself” the doctor replies. Shakespeare could never have conceived of the practice of psychoanalysis and yet he gave birth to it. Psychoanalysis is Shakespeare personified.

In Hamlet, Freud found the ultimate confirmation for his theory of the Oedipus Complex. For Freud, the Oedipus Complex is the basic motive of human history, explaining both public and private behaviours. Hamlet is the quintessential neurotic and we are all affected. Simply put, we repress our desires, especially our sexual desires, and they return to haunt us like the Ghost in his castle. Repressed ideas have to be uncovered and addressed so they do not return in unpredictable and terrifying manifestations. It is why people go to shrinks. It’s also why they go to Shakespeare plays, which are chocked full of repressed ideas which return with devastating consequences. Sex is an integral part of most Shakespeare productions. He never looks away from the dirty bits and this frankness is one of Shakespeare’s most important gifts to history.

No other writer is so widely disseminated. No other writer has shaped language or literature as much as Shakespeare. But who is the man? Shakespeare is everywhere but who is Shakespeare? We know amazingly little about the man. Even basic facts are obscure. We do not even know how to spell or pronounce his name! He left us six signatures with six different spellings, none of which is the spelling we use today.

Here are the few facts as we know them: He was born, baptized and schooled in Stratford, married at age 18, fathered 3 children, eventually left his family to become a successful actor and playwright in London and retired and died in Stratford.

If we are going to find the man it will be in his plays and sonnets. Nobody has ever left behind a richer or more complete record of thought on every conceivable subject and situation. Shakespeare manages to inhabit his characters so perfectly that they leave little trace of himself in their language. It is impossible to pin him down about what he thinks or who he was, but along the way we find out a whole lot about ourselves and who we are.

He could be anyone in words. His old woman is as convincing as his young man. His plays are sublime mysteries. They point at the world and Shakespeare huddles behind the mirror and the source of all of the genius remains hidden. As far and as deep as we go he just keep going. He simply leaves us face to face with all the dilemmas he presents. An astonishing thing about William Shakespeare is the apparent lack of any ego. The greatest artist in history absolutely wrote himself out of history. It is almost as if he brushed away his footsteps as he went along. The great mystery is how little we know about the man who knows us so well.

If you want to understand life, read Shakespeare and then discuss what you read. That, too, is the idea of these blog entries. You do not have to get it all. Just don’t be afraid of Shakespeare’s language or intelligence. You will get a good, raw story with characters you will recognize and themes, like jealousy and ambition, that any person can understand and appreciate. Simply read and listen closely to his language and do not over-analyze. You will recognize and understand much, because our sense of ourselves is engraved in the plays – and we cannot get away from this very far, even if we try.

Will Shakespeare deals with the essential archetypal characters, situations and institutions of human society and as long as they survive then the plays will continue to read us and our culture. So long as the English language survives William Shakespeare will be here because he is the language as we have come to know it. We go to his plays to hear the quintessential human voice.

Why has William Shakespeare lasted these 400 years? Partly, it is the infinitely rich and pleasurable language. Partly it is the exquisite and entertaining storytelling. Partly it is the many fully formed characters. And partly the clever meaning and deep truths contained within his works.

Shakespeare managed to satisfy the intellectuals and entertain the masses simultaneously. His works are constantly being reinterpreted. His plays are not relics. They channel passion and teach universal life lessons. When we mourn the loss of a loved one, as in Lear, or wrestle with madness or depression, like Hamlet or fall hopelessly in love, like Juliet… there is where we find our Shakespeare.

Every new actor, director, culture and time period must adapt and reinterpret Shakespeare so that he remains relevant, contemporary and always fresh. Radical new interpretations, on stage and in the cinema, will ensure that the power of his words is never diminished. Terrific examples abound. Kenneth Branaugh’s Love’s Labour’s Lost is portrayed as a 1930s newspaper-headlined musical… and it is simply brilliant. Romeo + Juliet stars Leonardo DiCaprio and is set in weapon-clad, violent, gang-ridden modern Los Angeles, using only the precise language from the original play itself. Again, pure genius. Hamlet has been marvelously portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch, David Tennant, Mel Gibson, Kenneth Branaugh, Christopher Plummer, Lawrence Olivier, Orson Welles and many, many others. A recent Richard III stars a chilling performance by Ian McKellen as Richard. In the past two years I have seen an entire female cast absolutely nail King Lear and caught Much Ado About Nothing at the Globe Theatre in London, directed as a Mexican Drug Cartel spoof. The point is that we simply must always escape the antiseptic Victorian era Shakespeare and get back to the passionate, energetic, bawdy, savage, rambunctious storytelling he himself brought to the stage around 1600.

Before we encounter each play please read at least a synopsis if time permits. Follow the story, notice the characters and be prepared to encounter some excellent passages and quotes.

Above all, be curious.

Experiencing Shakespeare can be infinitely pleasurable and interesting, as it possesses so much meaning and truth expressed in the most clever language ever written. He satisfies us as he did both the groundlings and the intelligentsia of his day. I will map out the essential storylines, examine the characters, suggest some themes, highlight some marvelous quotes and passages, make note of unique characteristics and recommend some excellent video clips. But before we get to the plays let’s examine the life and times of Will Shakespeare…